What high-performing Southeast Asian conglomerates do right

There is no doubting the importance of conglomerates in the economic success of Southeast Asia.

Accounting for 17% of market cap and 30% of capital expenditure, the region needs its conglomerates to grow and create value.

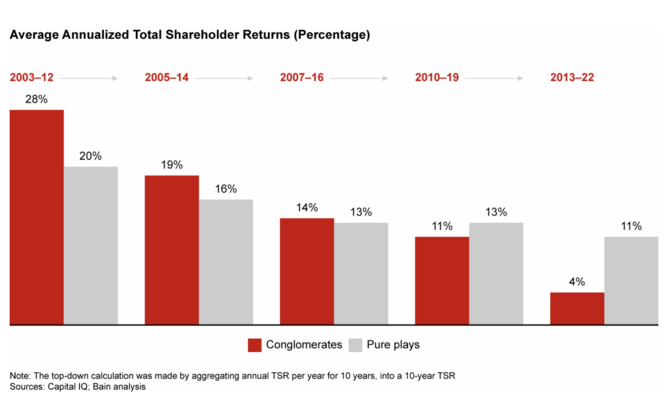

But over the last decade, conglomerates – which generate revenue from multiple categories rather than following a single business approach strategy – have significantly underperformed pure play companies, according to Bain’s latest report.

From 2013 to 2022, the average annualised total shareholder return was 4%, a 24-percentage point decline compared to the previous decade – while for pure plays, it was 11%, just 9 percentage points lower.

This widening of the performance gap between pure plays and conglomerates – which began in developed markets such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand in 2014 – is largely a result of conglomerates struggling to adapt to the lower-growth environment, Bain reports.

In short, they were slower to expand margins or exercise cost discipline to offset revenue losses, and their price-earnings multiples contracted.

And then the Covid-19 pandemic happened – sending new shockwaves of volatility across the economy and many conglomerates simply didn’t have the right combinations of speed, agility, and efficiency to thrive through the crisis.

In contrast, young and nimble pure plays were able to attract investors, government support, and talent by developing strong leadership positions in attractive sectors – they responded more quickly in the downturn, maintaining revenues, and lowering costs.

But not all conglomerates struggled.

The conglomerates outperforming their peers

According to Bain, over the last 20 years, a subset of 12 conglomerates have consistently outperformed their peers, securing top-quartile status for TSR growth across all economic cycles.

Referred to as ‘all-weather stars’, these conglomerates "increased revenue, defended their margins, and expanded multiples... even in lower-growth environments", according to Till Vestring, advisory partner at Bain in Singapore.

Among these twelve 'stars', Bain points to: Sinar Mas and Kalbe in Indonesia, BDMS Group, and DKSH Holding, both Thailand; Sunway Group, and Hong Leong Group, both in Malaysia; and Enrique Razon Group in the Philippines.

These, along with new stars including the PHINMA Corporation in the Philippines, Emtek in Indonesia, and VinGroup in Vietnam, all of which have businesses in essential sectors or high-growth areas, such as healthcare and renewables.

So, what actions did these conglomerates take to stay ahead of the game?

Bain’s research highlights five imperatives for Southeast Asia conglomerates:

1

Strive for strategic excellence in core business units

In Bain’s study, 44% of top-quartile companies are leaders in their primary business, compared to only 16% of companies in the bottom quartile.

“Companies should continue to reinvest in their core businesses to manage their strategic positions and offset erosion of the conglomerate advantage,” Bain says. And they should pursue leadership within their industries.

High-performing conglomerates manage their operational performance better, with 80% of top-quartile performers reducing their operational expenses as a percentage of revenue during the last decade compared to only 40% of bottom-quartile conglomerates.

2

Dynamically reshape portfolios to succeed in a volatile world

Top-quartile conglomerates actively reshaped their portfolios toward high-growth industries and growth engines of the future and are engaged in more M&A and divestitures to increase their exposure to growth sectors.

In top-quartile companies, about 35% of market cap was driven by high-growth sectors, compared to only 5% for the bottom quartile.

3

Redefine the corporate centre’s role

Bain identified two opposing approaches for corporate centres. The first, a ‘hands on’ approach where the corporate centre actively adds value to each business, so the value of the group becomes greater than the sum of its parts. The best corporate centers ‘pick their battles’ and develop distinct capabilities to capture synergies and support their portfolio companies.

In the other approach, the centre acts solely as an investment manager. The centre makes buy/hold/sell decisions, puts high-quality management teams in place, and fosters the right performance dialogue with each business unit. For this approach to work, conglomerates need small, disciplined, and highly skilled staff.

Which model is more suitable will depend on each group’s specific circumstances, but clarity on where and how to add value from the centre is paramount.

4

Invest heavily in innovation and technology

The top conglomerates invest heavily in technology and have become experts at using data analytics and automation to maximise top- and bottom-line productivity. Now, they are also leveraging technology to command a premium, shape new products and services, and generate new revenue streams.

In some cases, top conglomerates can even monetise their data and their proprietary data platform services. Winning with innovation and technology requires infrastructure, advanced tools, top talent, and strategic partnerships.

5

Optimise capital structures to reduce the conglomerate discount

Ownership and capital structure impact a conglomerate’s value in the public market. As Southeast Asia’s economies and capital markets have matured, investors have punished conglomerates, discounting their value by 7% to 43% compared to the sum of their parts. In response, several conglomerates have restructured to reduce the conglomerate discount and recapture value.

Ultimately, two distinct structures for conglomerates are likely to dominate the market. Type A, where the holding company is listed, and subsidiaries are fully owned by the holding company. Type B where the holding company is privately owned, with subsidiaries either partially listed or fully privately owned.

- Southeast Asia: path to profitability for digital companiesDigital Strategy

- Top 10 best-performing family businesses in Hong KongCorporate Finance

- Bain opens first Vietnam office amid digitalisation demandDigital Strategy

- Data science, management upskilling priority for employeesHuman Capital